Philae

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the ESA space probe, see Philae (spacecraft).

| Greek: Φίλαι; Arabic: فيله | |

|

|

| Location | Aswan, Aswan Governorate, Egypt |

|---|---|

| Region | Nubia |

| Coordinates | 24°1′15″N 32°53′22″ECoordinates: 24°1′15″N 32°53′22″E |

| Type | Sanctuary |

| History | |

| Builder | Nectanebo I |

| Founded | 380–362 BC |

| Abandoned | 6th century AD |

| Periods | Late Period to Byzantine Empire |

| Official name | Nubian Monuments from Abu Simbel to Philae |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii, vi |

| Designated | 1979 (3rd session) |

| Reference no. | 88 |

| Region | Arab States |

Map of Island of Philae, with floor plan of Temple of Isis.

as part of the UNESCO Nubia Campaign project, protecting this and other

complexes before the 1970 completion of the Aswan High Dam.[2]

Contents

Geography

Egypt - Scene, Phylae. Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection

Egypt - Ile de Phylae[?]. Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection

Panoramic view at the Philae Temple, at its current location on Agilkia Island

Lantern Slide Collection: Views, Objects: Egypt. Desert road to Philae, Upper Egypt., 1908., Brooklyn Museum Archives

Despite being the smaller island, Philae proper was, from the

numerous and picturesque ruins formerly there, the more interesting of

the two. Prior to the inundation, it was not more than 380 metres

(1,250 ft) long and about 120 metres (390 ft) broad. It is composed of Syenite stone: its sides are steep and on their summits a lofty wall was built encompassing the island.

Philae, being accounted one of the burying-places of Osiris, was held in high reverence both by the Egyptians to the north and the Nubians (often referred to as Ethiopians

in Greek) to the south. It was deemed profane for any but priests to

dwell there and was accordingly sequestered and denominated "the

Unapproachable" (Ancient Greek: ἄβατος).[9][10] It was reported too that neither birds flew over it nor fish approached its shores.[11] These indeed were the traditions of a remote period; since in the time of the Ptolemies

of Egypt, Philae was so much resorted to, partly by pilgrims to the

tomb of Osiris, partly by persons on secular errands, that the priests

petitioned Ptolemy Physcon (170-117 BC) to prohibit public functionaries at least from coming there and living at their expense. In the 19th century AD, William John Bankes took the Philae obelisk on which this petition was engraved to England. When its Egyptian hieroglyphs were compared with those of the Rosetta stone, it threw great light upon the Egyptian consonantal alphabet.

The islands of Philae were not, however, merely sacerdotal abodes; they were the centres of commerce also between Meroë and Memphis.

For the rapids of the cataracts were at most seasons impracticable, and

the commodities exchanged between Egypt and Nubia were reciprocally

landed and re-embarked at Syene and Philae.

The neighbouring granite quarries

also attracted a numerous population of miners and stonemasons; and,

for the convenience of this traffic, a gallery or road was formed in the

rocks along the east bank of the Nile, portions of which are still

extant.

Philae also was remarkable for the singular effects of light and shade resulting from its position near the Tropic of Cancer.

As the sun approached its northern limit the shadows from the

projecting cornices and moldings of the temples sink lower and lower

down the plain surfaces of the walls, until, the sun having reached its

highest altitude, the vertical walls are overspread with dark shadows,

forming a striking contrast with the fierce light which illuminates all

surrounding objects.[12]

Construction

Lantern Slide Collection: Views, Objects: Egypt - Philae. First court.,

n.d., This slide colored by Joseph Hawkes. Brooklyn Museum Archives

n.d., This slide colored by Joseph Hawkes. Brooklyn Museum Archives

Temple hieroglyphs on stone at Philae.

Lantern Slide Collection: Views, Objects: Egypt. Philae. les temples a Philae., n.d., Brooklyn Museum Archives

Trajan's Kiosk of Philae.

Egypt - Philae. Pylon., n.d., This slide colored by Joseph Hawkes. Brooklyn Museum Archives

Lantern Slide Collection: Views, Objects: Egypt - Philae. Great temple gallery., n.d., Institute Egypt. Brooklyn Museum Archives

Lantern Slide Collection: Views, Objects: Egypt - Philae. Temple of

Isis. Capitals of east colonnade., n.d., Joseph Hawkes. Brooklyn Museum

Archives

Isis. Capitals of east colonnade., n.d., Joseph Hawkes. Brooklyn Museum

Archives

Egypt - Philae. Columns., n.d., J. Levy & Cie Succrs. de Ferrier

Pere, Fils & Soulier, Paris. Institute Egypt. Colored by Joseph

Hawkes. Brooklyn Museum Archives

Pere, Fils & Soulier, Paris. Institute Egypt. Colored by Joseph

Hawkes. Brooklyn Museum Archives

Egypt - Temple of Philae. Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection

wealth. Monuments of various eras, extending from the Pharaohs to the

Caesars, occupy nearly their whole area. The principal structures,

however, lay at the south end of the smaller island.

The most ancient was a temple for Isis, built in the reign of Nectanebo I during 380-362 BC, which was approached from the river through a double colonnade. Nekhtnebef is his nomen and he became the founding pharaoh of the thirtieth and last dynasty of native rulers when he deposed and killed Nefaarud II.

Isis was the goddess to whom the initial buildings were dedicated. See

Gerhart Haeny's 'A Short Architectural History of Philae' (BIFAO 1985)

and numerous other articles which incontrovertibly identify Isis (not Hathor) as the primary goddess of the sacred isle.

For the most part, the other ruins date from the Ptolemaic times, more especially with the reigns of Ptolemy Philadelphus, Ptolemy Epiphanes, and Ptolemy Philometor (282-145 BC), with many traces of Roman work in Philae dedicated to Ammon-Osiris.

In front of the propyla were two colossal lions in granite, behind which stood a pair of obelisks, each 13 metres (43 ft) high. The propyla were pyramidal in form and colossal in dimensions. One stood between the dromos and pronaos, another between the pronaos and the portico, while a smaller one led into the sekos or adytum. At each corner of the adytum stood a monolithic shrine, the cage of a sacred hawk. Of these shrines one is now in the Louvre, the other in the Museum at Florence.

Beyond the entrance into the principal court are small temples, one

of which, dedicated to Isis, Hathor, and a wide range of deities related

to midwifery, is covered with sculptures representing the birth of Ptolemy Philometor, under the figure of the god Horus. The story of Osiris

is everywhere represented on the walls of this temple, and two of its

inner chambers are particularly rich in symbolic imagery. Upon the two

great propyla are Greek inscriptions intersected and partially destroyed

by Egyptian figures cut across them.

The inscriptions do not at all belong to the Macedonian era, and are of earlier date than the sculptures,[citation needed]

which were probably inserted during that interval of renaissance for

the native religion which followed the extinction of the Greek dynasty

in Egypt in 30 BC by the Romans.[citation needed]

The monuments in both islands indeed attested, beyond any others in

the Nile valley, the survival of pure Egyptian art centuries after the

last of the Pharaohs had ceased to reign. Great pains have been taken to

mutilate the sculptures of this temple. The work of demolition is

attributable, in the first instance, to the zeal of the early Christians, and afterward, to the policy of the Iconoclasts, who curried favour for themselves with the Byzantine court by the destruction of heathen images as well as Christian ones.[citation needed]

It's notable that images/icons of Horus are often less mutilated than

the other carvings. In some wall scenes, every figure and hieroglyphic

text except that of Horus and his winged solar-disk

representation have been meticulously scratched out by early Christians.

This is presumably because the early Christians had some degree of

respect for Horus or the legend of Horus - it may be because they saw

parallels between the stories of Jesus and Horus (see Jesus Christ in comparative mythology).

The soil of Philae had been prepared carefully for the reception of

its buildings–being leveled where it was uneven, and supported by

masonry where it was crumbling or insecure. For example, the western

wall of the Great Temple, and the corresponding wall of the dromos, were

supported by very strong foundations, built below the pre-inundation

level of the water, and rested on the granite which in this region forms

the bed of the Nile. Here and there steps were hewn out from the wall

to facilitate the communication between the temple and the river.

At the southern extremity of the dromos of the Great Temple was a smaller temple, apparently dedicated to Hathor;

at least the few columns that remained of it are surmounted with the

head of that goddess. Its portico consisted of twelve columns, four in

front and three deep. Their capitals represented various forms and combinations of the palm branch, the doum-palm branch, and the lotus flower.

These, as well as the sculptures on the columns, the ceilings, and the

walls were painted with the most vivid colors, which, owing to the

dryness of the climate, have lost little of their original brilliance.

History

Pharaonic era

A sphinx in Philae

Egypt - Philae. Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection

soldiers in their turn. The first temple structure, which was built by

native pharaohs of the thirtieth dynasty, was the one for Hathor.

Greco-Roman era

Relief of a Ptolemaic king at the Temple of Philae

Egypt - Philae. Land Grant. (Ptolemaie Land Grant)., n.d., Brooklyn Museum Archives

( 527-565 AD ). Philae was a seat of the Christian religion as well as

of the ancient Egyptian faith. Ruins of a Christian church were

discovered, and more than one adytum bore traces of having been made to

serve at different eras the purposes of a chapel of Osiris and of Christ.

1800s

The temple of Philae, from Description de L'Egypte, 1800

- The approach by water is quite the most beautiful. Seen from the level of a small boat, the island, with its palms, its colonnades, its pylons, seems to rise out of the river like a mirage. Piled rocks frame it on either side, and the purple mountains close up the distance. As the boat glides nearer between glistening boulders, those sculptured towers rise higher and even higher against the sky. They show no sign of ruin or age. All looks solid, stately, perfect. One forgets for the moment that anything is changed. If a sound of antique chanting were to be borne along the quiet air–if a procession of white-robed priests bearing aloft the veiled ark of the God, were to come sweeping round between the palms and pylons–we should not think it strange.

1900s

Aswan Low Dam

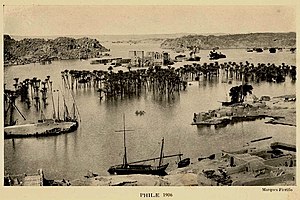

Philae flooded by the Aswan Low Dam in 1906.

Lantern Slide Collection: Views, Objects: Egypt. Kiosk. Temple of Philae, Egypt., 1908., Brooklyn Museum Archives

This threatened many ancient landmarks, including the temple complex of

Philae, with being submerged. The height of the dam was raised twice,

from 1907–1912 and from 1929–1934, and the island of Philae was nearly

always flooded. In fact, the only times that the complex was not

underwater was when the dam's sluices were open from July to October.

It was proposed that the temples be relocated, piece by piece, to nearby islands, such as Bigeh or Elephantine. However, the temples' foundations and other architectural supporting structures were strengthened instead. Although the buildings were physically secure, the island's attractive vegetation and the colors of the temples' reliefs were washed away. Also, the bricks of the Philae temples soon became encrusted with silt and other debris carried by the Nile.

Rescue project

General view of Temple of Philae, Egypt., 1908., Brooklyn Museum Archives

with each inundation the situation worsened and in the sixties the

island was submerged up to a third of the buildings all year round.

In 1960 UNESCO started a project to try to save the buildings on the island from the destructive effect of the ever increasing waters of the Nile. First, building three dams and creating a separate lake with lower water levels was considered.[13]

First of all, a large coffer dam

was built, constructed of two rows of steel plates between which a

million cubic meters of sand was tipped. Any water that seeped through

was pumped away.

a method that enables the exact reconstruction of the original size of

the building blocks that were used by the ancients. Then every building

was dismantled into about 40,000 units, and then transported to the

nearby Island of Agilkia, situated on higher ground some 500 metres (1,600 ft) away.

Nearby locations of interest

Prior to the inundation, a little west of Philae lay a larger island, anciently called Snem or Senmut, but now Bigeh.It is very precipitous, and from its most elevated peak affords a fine

view of the Nile, from its smooth surface south of the islands to its

plunge over the shelves of rock that form the First Cataract.

Philae, Beghé, and another lesser island divided the river into four

principal streams, and north of them it took a rapid turn to the west

and then to the north, where the cataract begins.

Bigeh, like Philae, was a holy island; its and rocks are inscribed with the names and titles of Amenhotep III, Rameses the Great, Psammetichus II, Apries, and Amasis II,

together with memorials of the later Macedonian and Roman rulers of

Egypt. Its principal ruins consisted of the propylon and two columns of a

temple, which was apparently of small dimensions, but of elegant

proportions. Near them were the fragments of two colossal granite

statues and also an excellent piece of masonry of much later date,

having the aspect of an arch belonging to some Greek church or Saracen mosque.

See also

- Abu Simbel - island and site

- Agilkia - island and site

- Bigeh - island and site

- Elephantine - island and site

- Aswan

- Diocese of Philae

- Luxor

References

- "Report on the safeguarding of the Philae monuments" (PDF). November 1960. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Philae. |

Further reading

- Arnold, Dieter (1999). Temples of the Last Pharaohs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512633-4.

- Dijkstra, Jitse H. F. (2008). Philae and the End of Ancient Egyptian Religion. Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-2031-6.

- Haeny, Gerhard (1985). "A Short Architectural History of Philae". Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale 85.

- Kockelmann, Hölger (2012). "Philae". In Dieleman, Jacco; Wendrich, Willeke. UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UC Los Angeles.

- Vassilika, Eleni (1989). Ptolemaic Philae. Peeters. ISBN 978-90-6831-200-3.

- Winter, Erich (1974). "Philae". Textes et langages de l'Égypte pharaonique: cent cinquante années de recherches, 1822–1972. Hommage à Jean-François Champollion. Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

External links

|

- Philae Satellite view @ Google Maps

- @ 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Sacred Temple Island of Philae

- Philae @ Mark Millmore's Ancient Egypt

- Philae @ EgyptSites

- Cruising the Nile: Philae

- Philae @ Akhet Egyptology

- Philae Temple Photos

|

|||

|

|||

|

||

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario